Note: This was originally sent to Hoop Vision Weekly subscribers on May 17th, 2019.

Please click/tap the button below to join the Hoop Vision community, for exclusive college basketball analysis, access, and research + the chance to interact with other hoop heads.

What Offseason?

Welcome back to the Hoop Vision Weekly!

We're back with Part 3 of our series on TRANSFERS; in the past two weeks we've spent some time looking at transfer trends in recent years, along with the specific conferences and teams that are affected most by transfers in and out.

Today, a look at graduate transfers and how these immediately eligible players perform for their new programs, and how star players at the low- and mid-major level perform after transferring "up" to a stronger program.

Here we go...

"Every bad team has a leading scorer"

...a college basketball axiom uttered in debates among coaching staffs across the country throughout the spring.

When a new transfer is announced -- or even just rumored -- a staff’s first step is to look at the player's stats. Naturally, even before diving into film and scouting reports and background due diligence, the statistics are a readily available resource and can quickly tell a coaching staff how the potential transfer stacks up in a list of 800+ names. Depending on the head coach, those stats could range from just basic per-game averages or KenPom tempo-free numbers. But regardless of the level of sophistication, stats are inevitably the first stop on short notice.

Upon diving into the stats, the coach is trying to contextualize and test assumptions. We know that 15 points per game in the MAAC is not the same as 15 points per game in the Big East, and while some might actually use that as an indictment on stats (or analytics) altogether, the reality is quite the opposite. The fact that a player averaged 15 points per game is a fact. It's descriptive of the player's previous season.

The role of analytics in the transfer process: contextualize.

This process of player projections across leagues or competition is crucial to NBA analytics thanks to what's at stake in the NBA Draft. The college transfer scene is quite a bit different. You're not drafting players, you're recruiting players; the decision has to be mutual. Of course evaluation is very important, but there's also a supply and demand component that should theoretically be leading to a more efficient market.

Perhaps the best candidate for this year's "every bad team has a leading scorer" cliche is graduate transfer Rayjon Tucker (Little Rock). Tucker averaged 20 points per game with a true shooting percentage of 64% on a 5-13 Sun Belt team. Tucker himself was actually very efficient, but his team was not. He committed to Penny Hardaway and will finish his college career at Memphis, provided he returns to school and does not remain in the NBA Draft.

You might know where this is headed if you saw my tweet from earlier this week:

Now you’ve seen it, but let’s refresh anyway and bring that image more into focus.

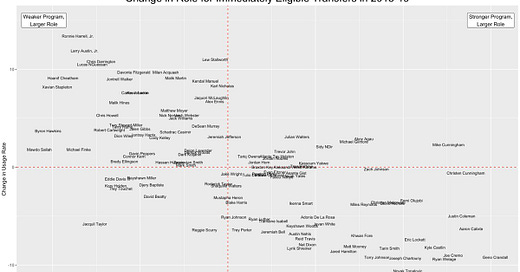

The graph below shows the immediately eligible transfers from the past season. The x-axis is the change in program strength; Geno Crandall, for example, is all the way on the right because he went from South Dakota to Gonzaga. The y-axis is the change in usage rate. Ronnie Harrell, for example, is all the way on the top because he went from using 15% of possessions at Creighton to 28% at Denver:

There's a fairly strong negative correlation between change in program strength and change in usage rate. In other words - when a star player at a smaller program transfers to a larger one, they play a less prominent role.

This shouldn't be a surprise: a player transferring up a level is probably going to have more talented teammates, reducing the transfer's role.

So how many "extreme" up-transfers do we get per year?

I defined "extreme" as any player that went to a program that has an average adjusted efficiency margin of at least 15 points per 100 possessions higher than the program they came from.

There have been 30 of these type transfers per year since 2012, but the number has increased over time, and dramatically so in the past two years.

This could be due to more "superstar" low and mid-major players deciding to transfer, but also the willingness of major programs to take transfers. Look no further than Roy Williams adding both William & Mary's Justin Pierce and Charleston Southern's Christian Keeling this offseason.

The player stats above (minutes per game, usage rate, and offensive rating) are from the transfer’s final year at his previous school. The average up-transfer played 28 minutes while using 23% of his team's possessions with an offensive rating of 101.

So what happens in year one at the new school?

That same average up-transfer played 21 minutes per game, while using 19% of his team's possessions with an offensive rating of 102.

Logically, it makes sense that minutes and usage would be more likely to significantly change than efficiency. Let's go back to the original Rayjon Tucker example. At Little Rock, he had a usage rate of 24% and an offensive rating of 114. With the amount of talent and depth on the Memphis team he'll be joining, it is likely that Tucker’s usage rate will decrease. But if we set the over/under for his offensive rating at last year's number of 114, I might be inclined to take the over. Tucker will be playing against better competition in a better league, but with more talented teammates. Ideally, Hardaway will find a role for his graduate transfer that maximizes not only Tucker's efficiency - but the team's overall efficiency.

And ultimately, that's the next step to this conversation. Every bad team does have a leading scorer...that's a fact. But the specific skill set of that leading scorer will help determine if he can turn into an effective role player at a higher level. Usage rate and offensive rating are a foundation for determining a player's overall role, but not always granular enough for the task at hand.

An interesting way to increase granularity is by grouping the data by position:

Size -- or at least, useful size -- is hard to come by in college basketball. In total, 16 up-transfers were identified as centers in the Verbal Commits database, and those centers had both the lowest usage rates and lowest minutes on their new team of any position.

Of course there are other reasons to take a lower-level big (rebounding and rim protection being the main two), but most of the research we have done in the past has showed that it's generally not a recipe for success if you're relying on a transfer center (whether it's a D1 transfer or a junior college transfer) to provide high-usage offense in a new system.

FEEDBACK? SUGGESTIONS?

What did you think about this new format for the newsletter? We'd love to hear thoughts!

Part of the goal of launching this newsletter is to gather feedback from you. We’ll hope to engage this community in the occasional poll, contest, or something else along those lines.

If you have any feedback on what you’d like to see from this, any general thoughts on the Twitter/YouTube/Podcast coverage...or anything really, please fill out THIS FORM.