Hoop Vision Weekly: Defending the Three (7/21/19)

2,000 words on three-point defense, helping one pass away, and Virginia Tech

Welcome back!

This is our second week of deep dives into the stats and film behind defensive theory and schemes.

Mailbag Q&A Coming Soon

A quick aside: before getting into today’s edition, you might have noticed (hopefully!) that more time and original research is being invested into the Hoop Vision Weekly this summer.

That’s not a coincidence; it’s an intentional choice, and it won’t be slowing down — quite the opposite, actually.

We want to keep growing and could use your help.

Forward this email to a friend, co-worker, or coach with similar interests and get them signed up for our email list.

Share on Twitter and social media.

On a related note, we also want to continue building a community feel around Hoop Vision. A lot of interaction occurs on Twitter and in email threads and text conversations — but we’d love to bring some of that into the light within this weekly newsletter.

So in two weeks, we’re going to try out a Q&A, mailbag-style newsletter.

Leave a comment with any basketball related question. Schemes, analytics, free throws out of 100, whatever.

Thank you for your continued support!

The existing literature on three-point defense

I’d argue that no public-facing college basketball analysis has been more influential than Ken Pomeroy’s work on three-point defense.

He started with a pair of scatter plots back in early 2012, coming to a conclusion that has had ripple effects throughout the sport:

(bolded emphasis in each of these passages is mine)

The following plots of that data should make it clear that opponents’ three-point accuracy is largely out of a team’s control.

That initial analysis turned into a longer article with even more scatter plots titled: “The 3-point line is a lottery.”

Ten months later, his conclusion was the same in another article on three-point defense:

When someone discusses three-point defense in terms of three-point percentage, they might as well make the leap to discuss free-throw defense in similar terms. Teams have much more control over how many threes their opponents shoot than how many they make.

Next, in 2013, Ken introduced “The Boeheim Exception.”

Syracuse’s zone had (and still has) a strong track record of three-point percentage defense. Ken speculated that this was more due to what Syracuse’s defense is doing in the paint rather than on the perimeter - in turn forcing teams to settle for threes. But even with this exception, the overall conclusions remained about the same:

In other words, you’d be better off assuming teams have no control over three-point defense than assuming swings over a two or three game stretch say anything about one’s defense. I’m willing to concede the Boeheim zone has some influence, but it’s small.

Finally, in “One last post on 3P% defense” Ken concluded the series with the following opinions:

The offense is largely in control of the quality of 3-point shots it takes.

These decisions are affected by the quality of the opposing 2P% defense

3P% is also influenced by effective challenging of shots.

All of that can add up to about a 3% swing from average.

So 3P% defense is not totally random

But a defense has considerably more direct impact on 2P% than 3P%.

There’s no question that the research in Ken’s articles has absolutely impacted coaches in the sport.

Not only have the findings changed how coaches measure three-point defensive success, but some have gone a step further and applied the philosophy to their defensive scheme.

3PA% is controllable, but should you even want to control it?

At first glance, the answer to the question above seems obvious.

We know from Ken’s work that defenses have control over the volume of three-point shots they allow.

We know that the NCAA average 3P% was 34.4% (1.03 points per shot) last season

We know that the NCAA average 2P% was 50.1% (1.00 points per shot) last season

If we can control how many our opponents shoot and it’s the more valuable shot, then let’s take it away - right?

The problem here is that — just like in our newsletter on ball screens — this is never a binary decision. A defense doesn’t simply decide “OK - this possession, no three-pointer will be taken.”

Instead, the defense chooses a scheme and coverage for the different offensive actions; it’s a game of probability and expected value from there. The general idea of taking away the three-point attempt doesn’t get you particularly far. There must be an application of the idea to a specific coverage.

Aside from the oft-discussed direct impact of the three-point revolution, it has also hurt defenses indirectly, by opening up the court with shooting gravity. The commitment to taking away the three-pointer puts a tremendous burden on your defense.

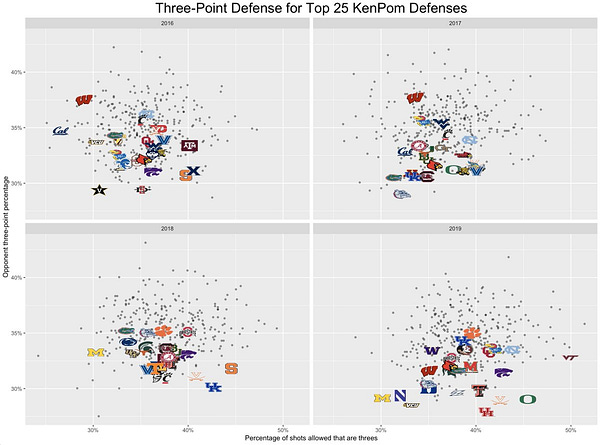

This line of thinking inspired a tweet earlier this week which highlighted the top 25 KenPom defenses in each of the past four seasons.

In the last four years, 54/100 “elite” defenses have been better than the NCAA average at taking away the three-point attempt.

There are plenty of different pathways to an elite defense, and this past season in particular showcased an especially wide range of those pathways.

Michigan (under now ex-coaches John Beilein and Luke Yaklich) set the standard for three-point defense with their “no help unless necessary” philosophy. But several of the other elite defenses had principles in their schemes which don’t prioritize three-point defense:

Texas Tech practically dared opponents baseline and then aggressively helped and rotated on the weakside

Houston double teamed the post

Virginia aggressively hedged ball screens

Oregon turned their season around with a matchup zone

And that’s not even to mention Virginia Tech, whose indifference to guarding the line (49.9% of opponent shots were threes) was extreme enough to make them a focal point for the rest of this newsletter.

Not all threes are created equal…but the offense knows that too.

Let’s take this from an abstract idea to a real scenario.

Imagine you have to choose a coverage for defending Michigan’s spread ball screens. They have Zavier Simpson (31-percent 3P%) using the ball screen, Jon Teske (73-percent 2P% in rolls) rolling to the basket, and Iggy Brazdeikis (39-percent 3P%) lifting up in the strong side corner

The most effective coverage to reduce the probability of the ball handler (Simpson) taking a three would be to hedge or blitz the ball screen.

The least effective coverage to reduce the probability of the ball handler (Simpson) taking a three would be to go under the ball screen.

On a surface level, hedging might seem like the best option to defend the three.

The problem, of course, is that hedging would also require Brazdeikis’ man to help or tag off of Brazdeikis, in order to give support on the roll.

Going under the screen has the opposite effect. You are conceding an off-the-dribble three to Simpson, so that you won’t need to give any help off of Brazdeikis.

This concept — potentially giving up a three with the goal of preventing an even-higher efficiency three — is common in many aspects of defensive scheme.

So why, then, is defensive three-point percentage not controllable?

Well, because Simpson doesn’t have to shoot. Maybe Michigan recognizes the under coverage and re-screens to give Simpson another chance at getting downhill. Or maybe he just reverses the ball to get to the next action.

In that example, both the shooter and the play type are relevant to the expected value. Not only is Simpson a less potent shooter than Brazdeikis, but shooting off the bounce is a worse shot than shooting off the catch (all else equal).

Now let’s move on from the Michigan scenario and focus on Virginia Tech. As previously mentioned, the Hokies gave up just as many threes as twos last season - and yet still finished #20 in adjusted defensive efficiency.

We can look at which type of players were the beneficiaries of Virginia Tech’s three-point negligence.

Each point above represent the individual players for Virginia Tech opponents. The x-axis is the player’s season average in 3P% (not including Virginia Tech games). The y-axis is the player’s 3PA per game.

If the point is red, that player increased their three-point volume (relative to season average) when playing against Virginia Tech.

Blue point means a decrease in volume vs. VT.

Gray means the volume remained about the same vs. VT.

If you’re Virginia Tech, you would like the red dots to be on the bottom left. This would indicate that players who don’t normally take or make a lot of threes were taking a lot when playing against the Hokies.

While that wasn’t exactly the case, there is a noticeable lack of red dots to the right of 40%. So while Virginia Tech’s defense was not typically forcing total non-shooters into high volume shooting roles, the Hokies were at least keeping the elite shooters (+40% from deep) to shooting levels near their typical volume.

The intentions of “no help one pass away” are good, but it’s more nuanced than that.

One coaching axiom that has emerged from the “take away the attempt” three-point movement is “no help one pass away.”

Some view this rule as a non-negotiable, and—to be fair—the intentions behind it are good. If a defender helps one pass away, it becomes easier for the ball handler to make the correct read. The open man appears in the passer’s line of vision, often spotting up for a high-efficiency three.

So while there’s often overlap between “don’t give up catch-and-shoot threes to capable shooters” and “no help one pass away”, the latter is a bit oversimplified.

First of all, there are different levels of “help.” A large chunk of college teams at least “stunt” one pass away - jabbing at the ball handler before returning to their man. But there are even situations where positive expected value exists from fully helping one pass away.

We saw that come to fruition in nearly every Duke game this season, thanks to having two of the best one-on-one players in all of college basketball and very little shooting:

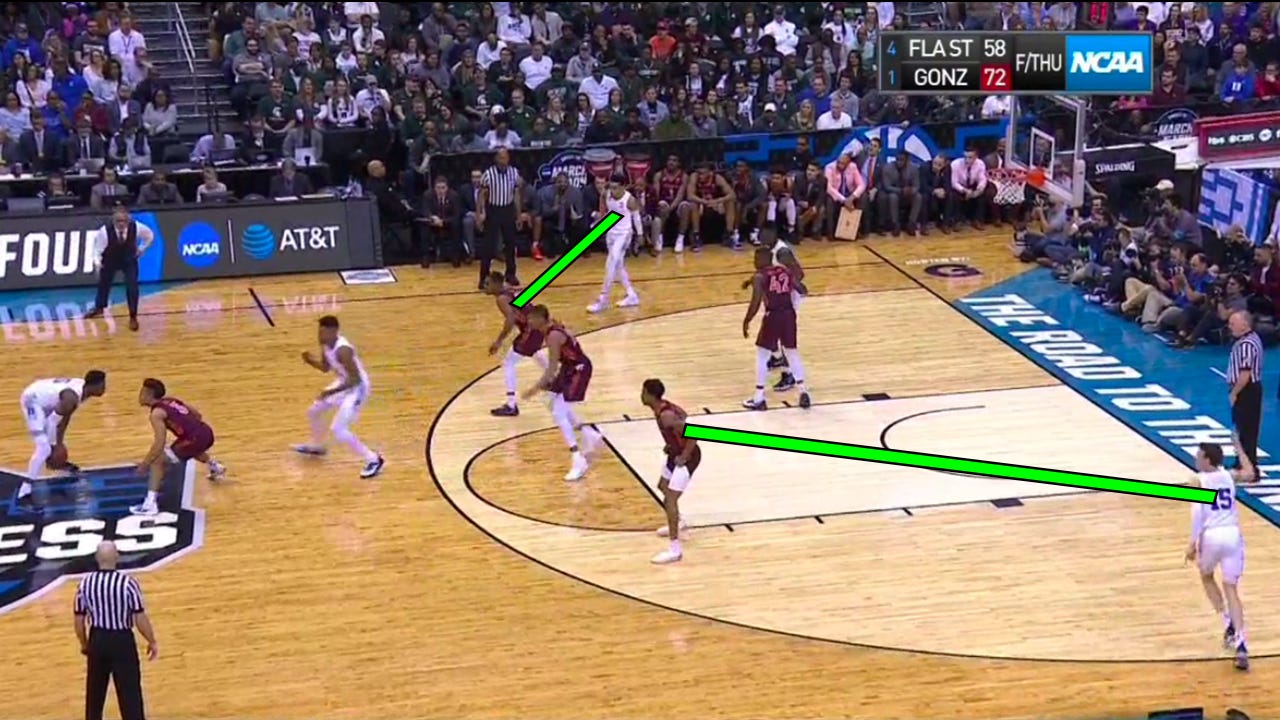

The video above showed Virginia Tech’s desire to consistently help one pass away against Duke in the regular season; they doubled down on that during the rematch in the NCAA tournament.

But don’t be fooled —Virginia Tech wasn’t helping one pass away just because of Duke’s personnel. This was the foundation for their base defense the entire season.

Virginia Tech held opponents to 0.55 points per isolation play on the season - #1 in the country.

RJ Barrett (11), Chris Lykes (9), Carsen Edwards (7) all had their season high in assists against Virginia Tech. Ty Jerome (12) had his second-highest season total.

By shrinking the floor and helping one pass away, Virginia Tech was able to limit the dribble drive abilities of opponent stars. They also ranked #26 in the country in defensive turnover rate and #22 in the country in defensive free throw rate.

Here are the Hokies in the NCAA tournament against Liberty, generating turnovers off of their help from one pass away:

The extreme help creates turnovers if the driver is insistent on getting in the gap. It also allows the weak side to not help as much. Since Virginia Tech had so much help one pass away, the low man (and/or rim protector) had a reduced role in the scheme.

That’s not to say that helping one pass away always favored the Hokies. Below, you’ll see a play off which Liberty scored nine points in the first half of that same game. Liberty’s offense was able to generate open catch-and-shoot threes by spacing the one pass away helper out.

The overall implication here is by no means that Virginia Tech unlocked some revolutionary or secret defensive scheme this season.

Shrinking the floor and making the ball handler see bodies has long been valued by coaches, but that trend has actually moved in the opposite direction in recent years.

Isolation, post-ups, and one-on-one situations tend to be inefficient, and that’s at least in some part due to defenses shrinking the floor. Yet Virginia Tech’s desire to deter those inefficient play types from happening does feel flawed.

Almost nothing puts a heavier burden on a defense than strong three-point shooting; the extra point makes it highly efficient. But it’s about finding the right balance for your team between taking those highly-efficient jumpers away and still providing support to the ball.

Virginia Tech was surprisingly successful in 2018-19 while leaning heavily towards “providing support to the ball” end of the spectrum.