Hoop Vision Weekly: Quantifying Defensive Scheme (7/14/19)

The statistical effects of pack line vs denial defenses

For the last several weeks, we’ve used this space to analyze offensive schemes and play type data. This week, we shift that focus to the defensive side of the ball.

In this edition we’ll explore:

The correlation between defensive efficiency and isolations

The statistical differences between gap defenses and denial defenses

How these concepts apply to scouting and gameplanning

Elite Defenses Force Isolations

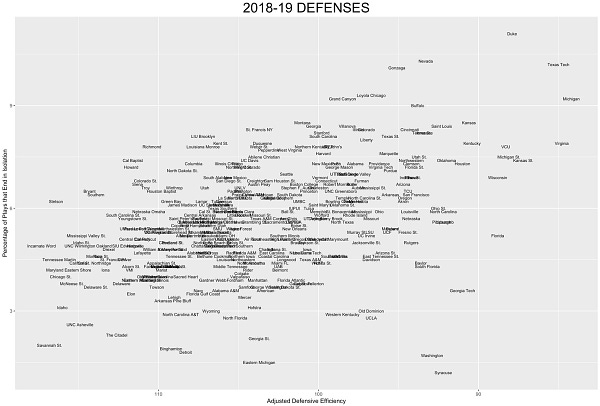

To start, let’s take this back to January when we first looked into defensive play type data. We found that a team’s ability to force opponents into a high volume of isolations was a reasonably good identifier of elite man-to-man defenses.

It’s easy to shape a narrative around why this is the case.

Elite defenses are able to stall the primary action of their opponents (think motion screens or ball screens), forcing late-clock or panic situations which lead to iso-heavy, low efficiency offense — and that narrative may seem obvious after looking at the graph above.

One might also try to shape a narrative for the opposite stance; poor defenses could be so poor that offenses don’t even need their primary action to be efficient - they just go straight to iso ball (Spoiler: the numbers don’t support this narrative, so forget about it).

—————

For this newsletter, there are a couple wrinkles we can add, in order to improve on that original January tweet:

Filtering out the teams that play zone or press at a high frequency

Controlling for opponents

Zone and press defenses have such strong influence on opponent play types, they really deserve their own newsletter entirely. But for this one we are going to focus on the different types of man-to-man schemes.

Controlling for opponents helps take care of any case where a team, even by coincidence, happened to have a bunch of isolation heavy offenses on their schedule.

After making these adjustments, here were your top five teams at forcing isolations for the 2018-19 regular season:

Nevada

Gonzaga

Duke

Illinois

Texas Tech

STUDY HALL: Film & Breakdown — Elite Man-to-Man Defenses

There are certainly some similarities in scheme between those five.

Illinois plays maybe the most aggressive brand of halfcourt man-to-man defense in the country with exaggerated denials and ball pressure. Duke has some of that same philosophy, albeit with different execution.

Nevada and Gonzaga switched ball screens at all five positions, unlocking some of the defensive versatility of their lineups.

Texas Tech, the best defense in the country, was able to do it all. They both switched and iced ball screens and used more situational denials.

An interesting note about Texas Tech is that the isolations primarily occurred against guards. There were 13 players in the NCAA that were isolated at least 50 times last season. Nevada big Tre’Shawn Thurman made the list. Gonzaga bigs Rui Hachimura and Brandon Clarke made the list. Duke big Marques Bolden and combo forward Jack White made the list. Texas Tech was the only team with three players on the list, but it was their starting perimeter players: Davide Moretti, Matt Mooney, and Jarrett Culver.

It’s pretty intuitive that switching and denying will lead to isolations. And marginally speaking, the data supports that.

But if we go just slightly further down the isolation list, you’ll find teams like Virginia at #8 and Michigan at #10. Both were elite defenses, but much more traditional pack line or gap style.

The moral of the story here is that, regardless of scheme, elite defenses still tend to force isolations. The switching and denying (especially at the extremes) can help add to our ability to predict isolations, but the strongest variable in that prediction is overall defensive strength.

Gap Defenses vs. Denial Defenses

Isolations aren’t the only play types that defenses have some control over.

Consider off-ball cutting action; denial defenses are essentially daring you to cut. It’s Basketball 101: If your man is overplaying you, then cut backdoor.

The other side of that coin is gap defense, the most famous being Virginia’s pack line. Defenders are in the gap providing help to the ball handler instead of denying their own man. Driving lanes are hard to come by, but the defense is mostly free to pass the ball around the perimeter.

Using the same methodology as in the previous section, we can determine the five defenses which most suppressed cutting action.

Wisconsin

Colgate

Air Force

UMBC

Louisville

As you might expect, the top of the cutting list is a very good indicator of gap defense.

For me, there are three current high-major coaches that immediately come to mind when thinking gap or pack line: Tony Bennett (Virginia ranked #22 in cut suppression), Sean Miller (Arizona #6), and Chris Mack (Louisville #5).

Retired Wisconsin coach Bo Ryan would be another that comes to mind, but it looks like his successor Greg Gard should be added to the list, as Wisconsin was #1 at suppressing cuts by a healthy amount.

So what other play types are impacted by the decision to gap or deny?

To answer that question, we need to find a way to quantify defensive aggressiveness (gap vs. deny) without using play type data.

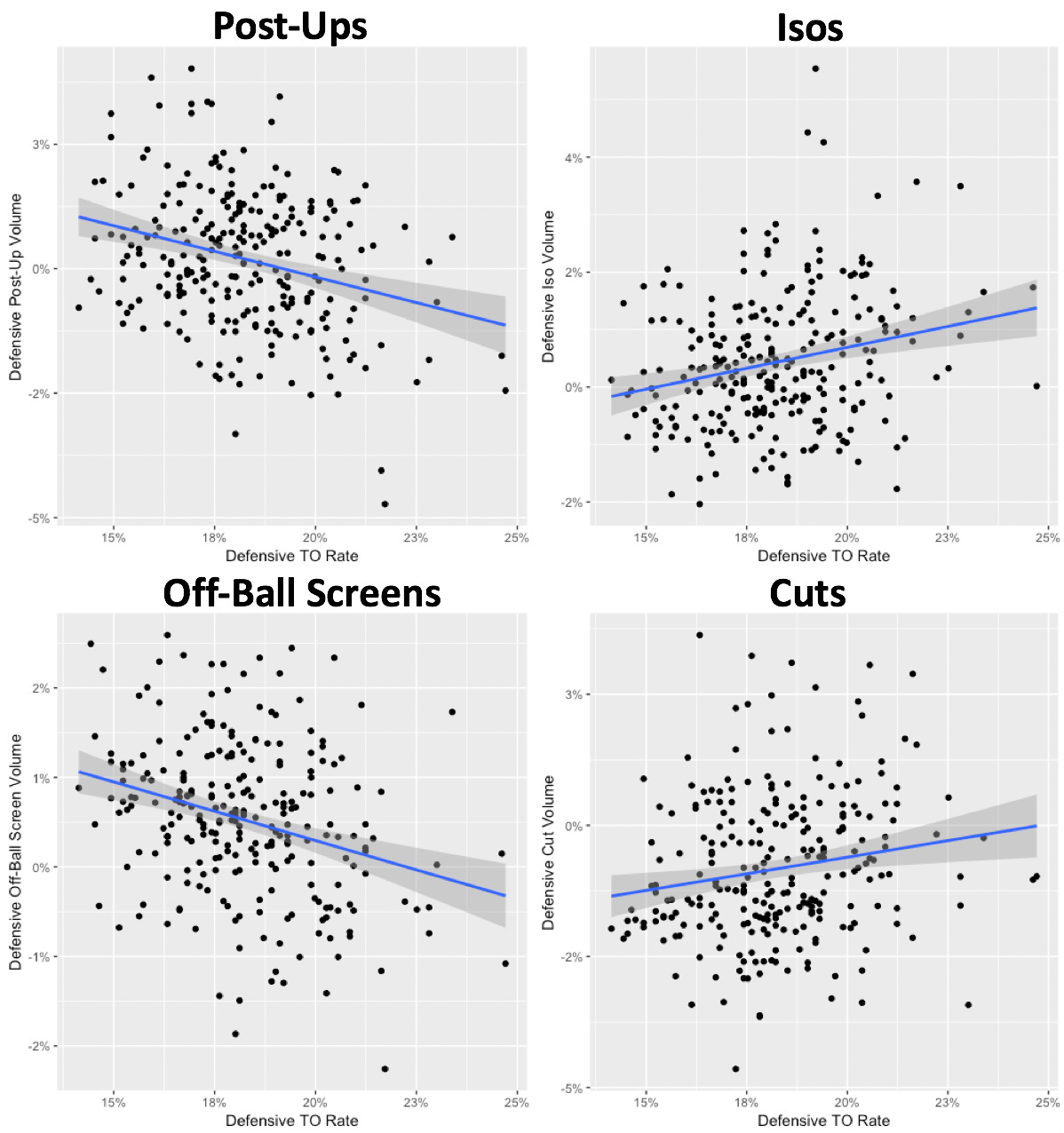

Defensive turnover percentage is the most obvious candidate amongst traditional box score stats. And while it’s by no means a perfect measure, it’s used below as a proxy for aggressiveness:

It should be noted that that while these correlations do exist, they aren’t extremely strong. In fact, all four are weaker than the correlation described in the first section between isolations and overall defensive efficiency.

But as a very general rule, here are the conclusions to be drawn from the play type data:

Gap defenses (low turnover rates) increase the frequency of post-ups and off-ball screen action - both of which tend to require entries to the wing.

Denial defenses (high turnover rates) increase the frequency of isolations and off-ball basket cuts.

Play Type Suppression and Scouting

Seeing the concept of “defensive schemes influencing offensive play types” written out formally might seem somewhat new or advanced, but it’s really one of the main goals in scouting and gameplanning.

The coaching staff identifies all of the different plays and actions that an opponent runs and then choose how to defend them. Teams have a “base defense” that consists of their general principles and responsibilities, but that base defense can be altered depending on the specific opponents scheme and personnel.

The concept of scout defense (and more specifically - situational denials) was covered on a Solving Basketball episode with my former boss — New Mexico State head coach Chris Jans.

When a defense chooses to take something away, it’s important to consider the alternatives. A potential cognitive bias in coaching emerges from trying to “out-coach” your opponent, as opposed to trying to maximize expected value.

The example I like to use here is the baseline out of bounds screen-the-screener play.

There’s a general perception that dead ball situations are an ideal platform for a coach to show their worth (notable case in point: Brad Stevens). Likewise, getting beat on an out of bounds play may be viewed as a sign of a team/coach being under-prepared.

It’s fairly standard practice for gameday shootarounds to include a final overview of the opponent’s baseline out of bounds plays and assign a coverage.

Screen-the-screener is a specific type of BLOB play that (usually) involves a shooter starting on the weak side, setting a screen for another player, and then receiving a screen to move towards the strong side corner for a potential jump shot.

Of course there’s no shame at all in making sure your team is well-prepared for these situations. But I think there are some scenarios in which it would actually be a positive expected value decision to persuade the offense into taking that contested mid-range jumper - instead of using a coverage which simply takes it away.

In this specific instance it depends on not only the shooter, but also the overall halfcourt efficiency of your team and your opponent.

But the larger point here is: Just because your opponent is doing something, doesn’t mean it’s necessarily in your best interest to stop that thing.

FEEDBACK? SUGGESTIONS?

Part of the goal of launching this newsletter is to gather feedback from you. We’ll hope to engage this community in the occasional poll, contest, or something else along those lines.

If you have any feedback on what you’d like to see from this, any general thoughts on the Twitter/YouTube/Podcast coverage...or anything really, please fill out THIS FORM.