How do you score against Texas Tech? (HV+)

Three rules to optimize baseline drives against the Red Raiders

The #1 ranked defense of the century

Texas Tech’s defense came out with a bang last season — and then never really relented. The Red Raiders finished number one in KenPom’s adjusted defensive efficiency. They were also the best recorded defense in Ken’s system since 1999.

In the world of Hoop Vision, we took a deep YouTube dive into Chris Beard’s no-middle scheme during the NCAA tournament:

Why Texas Tech and Michigan are the Best Defenses in College Basketball

The first seven minutes of that video cover the Texas Tech scheme and personnel in detail. They also looks at some different ways Buffalo tried to attack the defense.

The big question that’s been on my mind in the off-season (which I also asked Texas associate head coach Luke Yaklich in a recent episode of Solving Basketball) about Texas Tech’s defense is simply:

Should you just take what they are giving you and drive baseline, or resist the urge?

In an attempt to inject some data into the conversation, we watched every spot-up three-pointer allowed by Texas Tech last season and charted the root cause.

Theoretically, middle drives are the kryptonite of the Texas Tech defense. The scheme isn’t built to effectively handle the ball getting into the middle of the paint. Middle drives lead to Red Raiders being forced to help one pass away — which leads to catch-and-shoot threes.

The problem for opponents, however, is that they can’t get into the middle in the first place. Texas Tech allowed just 1.8 points per game on threes generated via middle drives.

So maybe my initial question is a bit misguided. Regardless of if an opponent wants to drive baseline, Texas Tech is going to force them to do just that.

With that in mind, we will now look at three essential concepts to optimizing baseline drives against a Texas Tech team that is in a class of its own at defending them.

Three rules to optimize baseline drives against Texas Tech

#1) Snake the ball back to the middle when they give you “too much baseline”

There are many college basketball defenses with a preference for keeping the ball out of the middle, but Texas Tech goes way beyond just influencing to the baseline — they force it.

In order to force the ball baseline, the on-ball defenders adjust their foot angles. Those foot angles can sometimes get so extreme, the defender’s whole body essentially faces the sideline.

When that’s the case, savvy ball handlers can start their drive to the baseline — but ultimately “snake” the ball back into the middle. Examples of the “too much baseline” concept are included in the video below.

Perhaps the time Texas Tech is most vulnerable to a snake back to the middle is after a long close-out. Their defenders are trained to close-out to the high side and take away the middle, but it can be difficult to execute at full speed.

#2) Occupy and distort the first helper

Inevitably, you are going to be forced to drive baseline against Texas Tech. So if the ball handler can’t snake it back to the middle, these last two rules help optimize that more traditional baseline drive.

On every baseline drive, Texas Tech’s scheme calls for an early help defender to (aggressively) meet the ball — preferably outside of the paint.

We have already talked about how extreme the on-ball defender’s foot angles get. The reason the Red Raiders can get away with that is because of the “first helper”. Even if a driver gets a step on his man, he’s going to be met by a help defender looking to take a charge, block a shot, or just stop the ball.

One tactic used by Virginia in the national championship was to “lift” the offensive player being guard by the “first helper” (aka the low man).

Generally speaking, the Chris Beard philosophy is that over-helping is better than under-helping. So even when you distort the first helper, chances are someone is still going to step up.

Still, the distortion at least increases your probability of causing an incorrect rotation — which Texas Tech is normally so precise with.

#3) Prioritize weakside spacing over just about everything else

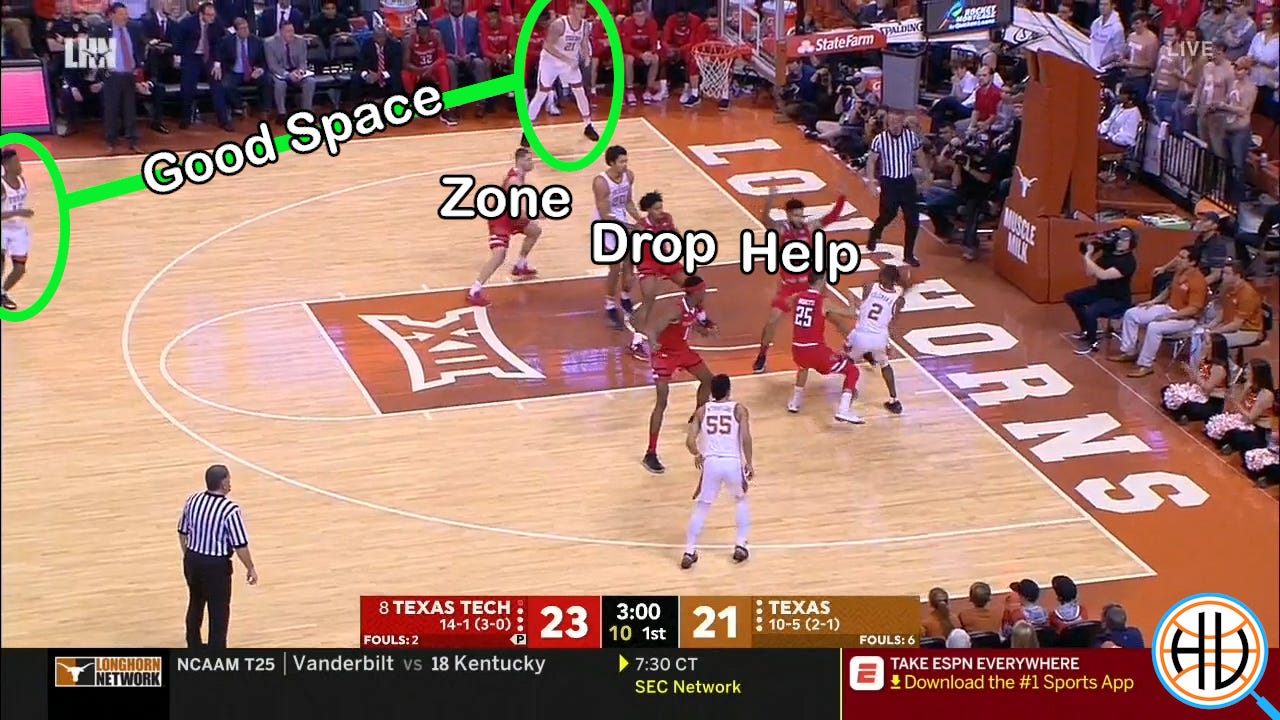

The last rule is, in my opinion, the most important. Let’s suppose you drive baseline and Texas Tech executes their coverage:

The “first helper” meets the driver outside the paint

The “dropper” sinks to the level of the ball and protects the basket

The “zoner” splits the difference between the two weakside perimeter players

That execution would look something like this:

This is exactly how it’s supposed to look for Texas Tech.

Moretti has forced the ball baseline, but at the same time stayed tight to the ball

Francis (first helper) has met the ball outside the paint

Edwards (dropper) has dropped to the level and gotten inside of the Texas big (Sims)

Mooney (zoner) has split the difference between the two weakside perimeter players — essentially playing a zone

And yet with all of that execution, Texas is still able to make a simple pass out for a wide open three (see video further below). The reason is spacing.

As good as the Tech defense is, it’s not magic. By sending early help (and more or less doubling the ball), they are trusting Mooney to guard two players at once on the weakside. That’s a much more difficult task for Mooney when the perimeter shooters are spread out.

The optimal spacing for an opponent driving baseline against Texas Tech — like the one pictured above — is something like this:

Player 1 filling behind on the drive — taking a Tech defender (in this case Owens) out of the play entirely

Player 2 cutting to the basket — forcing the Tech “dropper” (in this case Edwards) to stay glued to the hoop

Player 3 spotting up as deep in the corner as possible for a baseline drift pass

Player 4 spotting up right at the top of the key — causing the “zoner” responsible for guarding both Player 3 and Player 4 (in this case Mooney) to have the longest close-out possible

Examples of good spacing (and one example of not so good spacing) are in the video below.

Tomorrow, we continue with Texas Tech’s defense. Answering the question: Should more teams be aggressively forcing the ball to the baseline?

And one of (if not) the mastermind behind the defense — Mark Adams — is now a top paid assistant.

https://www.lubbockonline.com/news/20191002/tech-raise-could-make-adams-nations-second-highest-paid-assistant