Kryptonite or Cliche?

Examining a popular theory on how to bust the 2-3 Syracuse zone.

Welcome back to the Hoop Vision (semi) Weekly — coming to you on a Monday this week.

As students return to college campuses and non-conference schedules begin to slowly get announced, we begin our countdown to the college basketball season: 78 days until the 2021-22 regular season begins.

Today, we take a look at one of the most closely scrutinized schemes in college basketball — the Syracuse 2-3 zone — and the idea that it can be beat simply by getting the ball into the high post.

Note: Today’s newsletter is sponsored by The Power Rank, a FREE football analytics newsletter that strives to be valuable, concise and entertaining while providing data-driven betting information on the NFL, college football, and March Madness. Check out more info on The Power Rank later in this newsletter.

If you’re subscribed to this newsletter, we’re assuming that you have a working knowledge of the famous (or infamous, depending who you ask) Syracuse 2-3 zone. The defense has become an enduring calling card for Jim Boeheim’s program, now existing as a novelty in the modern college game.

When Syracuse has a widely televised game, broadcasters often claim that the opponent’s best course of action is to “get the ball to the high post” against the zone — as if success against the zone is just that simple.

In all fairness, a 1-3-1 offense — with a player flashing into the foul line area — is the most common attack against a 2-3 zone. So naturally, there is some truth to the importance of playing through the high post.

Still, it’s often portrayed as if the high post is Syracuse’s kryptonite.

Let’s not limit ourselves to in-game commentators here; beat writers and fans alike seem to believe Boeheim and his team have never even considered what might happen if the ball finds its way to the sacred high post area.

Spoiler: Jim Boeheim is ready for teams who aim to play through the high post.

First and foremost, Syracuse makes it difficult for an offense to comfortably get the ball into the high post. The Orange are — by design — consistently one of the tallest and longest teams in the country. Last season, Syracuse ranked 28th in kenpom’s average height, which was actually their smallest team since the 2008-09 season.

Second, Syracuse almost always has a long and lanky center playing the bottom of the zone. The foul line area isn’t the most efficient shooting area to begin with, particularly with a 7-footer roaming the area. That allows the rest of the Syracuse defenders to “fan out” (more on that in the next section).

And finally, Boeheim has noted in the past how shots from the high post are the easiest for Syracuse to rebound from a positional perspective.

That’s not to say the Orange can’t be beat by playing through the high post, but it’s a game of cat and mouse, with Syracuse and its opponents making adjustments accordingly.

In the sections below we will look at a few of those adjustments:

Syracuse’s base defense when the ball goes into the high post: Fanning out to shooters

Hi-Lo offense after lifting the Syracuse forwards

A “dive and slide” concept used by Virginia after entering to the high post

Fanning out to shooters

If the ball gets into the foul line area against the zone, Syracuse’s center has the primary responsibility of containing the ball.

The skill set of the offensive player in the high post helps determine just how aggressive the Syracuse center must play the ball. But ideally he uses his length to stop the ball while also not completely vacating the paint.

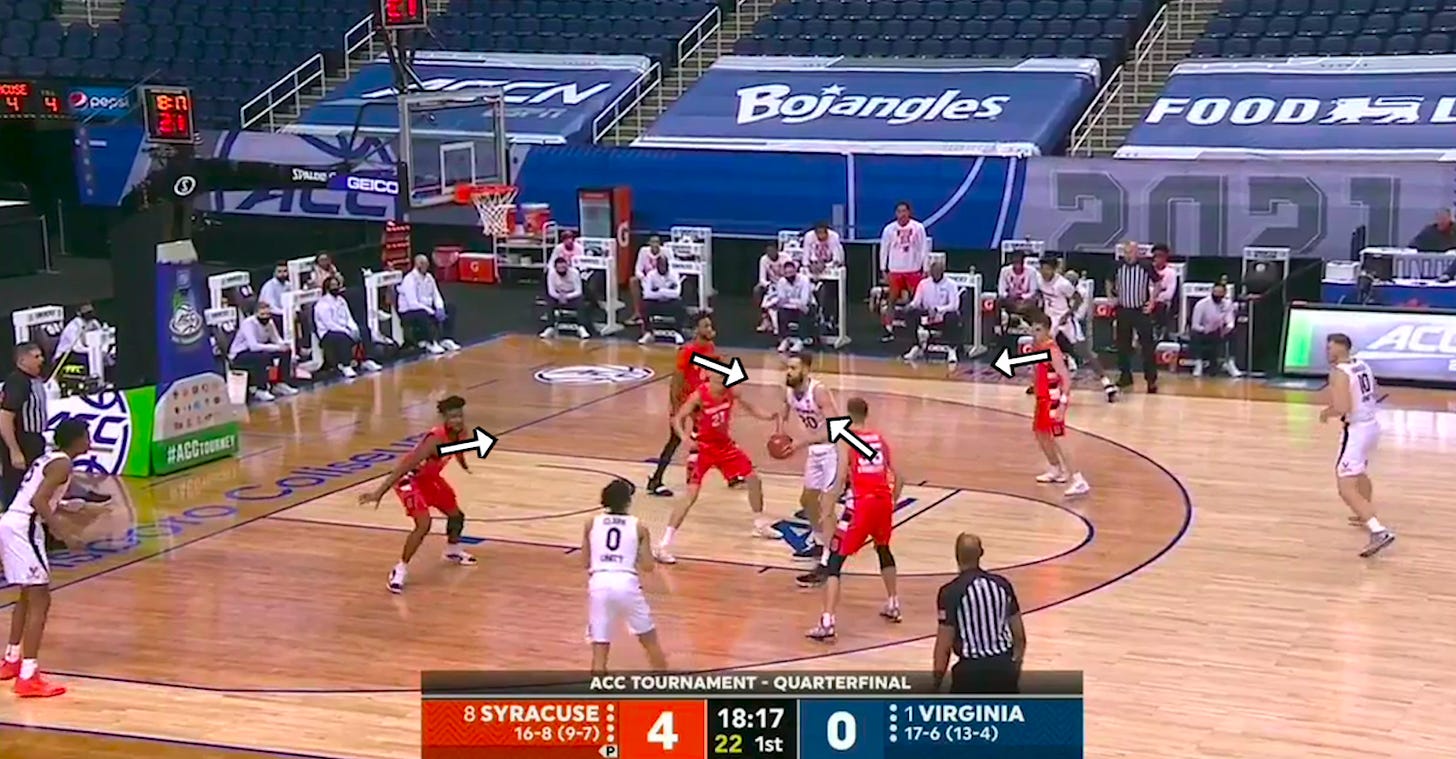

In the screenshot below, #21 Marek Dolezaj is playing the center position. With the ball in the high post, notice the positioning of Syracuse’s four other defenders.

The Syracuse off-ball defenders have essentially built a squared around high post. They face the ball with their chests, but then “fan out” to shooters as the play progresses.

Here’s an example from later on in that same ACC Tournament game against Virginia. With Virginia in a 4-out formation spread around Jay Huff, Syracuse’s defensive priorities are especially apparent.

With three Virginia players moving along the perimeter to the weak side, the Syracuse defense practically looks like man-to-man. The Orange prioritized taking away the shooters and relied on Dolezaj guarding Huff one-on-one.

So in Syracuse’s base defense — especially against teams with strong three-point shooting — the Orange look to force opponents into one-on-one play out of the high post.

In the clip above, Huff finishes after a great take to the basket — but most college bigs will not have his ability to put the ball on the floor and attack.

Hi-Lo against lifted forwards

As the three-point line has become a more important part of the game, the forwards in Syracuse’s zone have been forced to lift up progressively higher — particularly when the ball is out at the top of the perimeter.

Below is an especially extreme example of Syracuse’s lifted forwards. Notice how #0 Alan Griffin and #1 Quincy Guerrier are positioned above the foul line.

When the ball is out at the top of perimeter, the zone can sometimes look more like a 4-1 — with the center alone in the paint — than a 2-3.

Of course, that potentially leaves the paint open for a Hi-Lo opportunity if the opponent can get the ball to the foul line while the forwards are still lifted.

Syracuse aims to combat the Hi-Lo with two main concepts:

When the ball is at the top of the perimeter, they don’t allow the entry pass into the high post. The guards have to take that pass away

When the ball gets passed to the wing, the forward provides some initial support but is then “bumped” back down towards the paint

It’s great in theory, but not always attainable in live action.

Below you’ll see an example where the first rule is violated. Houston enters the ball directly into the high post from the top.

With #14 Jesse Edwards in the game, Dolezaj is playing the forward spot instead of center. He anticipates the pass to the wing, lifting up to give support on the ball. But when the ball goes to the high post instead, Houston has an easy dunk on the Hi-Lo with Dolezaj out of the play.

Next up, an example where the second rule is violated. The ball goes to the wing this time, but #0 Griffin doesn’t get bumped back down towards the paint.

The better the three-point shooter, the farther the Syracuse wing defender is forced to come out towards the perimeter.

But Griffin doesn’t have that excuse on the play above. The NC State player on the wing (#1 Dereon Seabron) was just 5-for-20 from three last season.

Hitting the high post while the forwards are still lifted is one of the best ways to put Syracuse in a compromised position in the paint. But as long as Syracuse is following their principles, it’s easier said than done.

Dive and Slide

This next concept from Virginia fully illustrates the chess match that takes place against the Syracuse 2-3 zone.

Virginia had a set play against Syracuse where they flashed point guard Kihei Clark in the high post area. As we’ve already covered, that high post flash is the center’s responsibility.

But now take a look at the rest of the play.

While Clark is flashing towards the foul line, Huff dives to the basket — setting up a potential Hi-Lo opportunity.

Alan Griffin is the weak side forward, so his responsibility is to drop on the dive to take away Huff. That clears out the weak side corner, and the Virginia perimeter players slide toward that corner. The play generated an open three, but Beekman hoisted up an airball.

Here’s the same play again, later in the first half.

It’s a tough play for Syracuse to guard, but it brings up another concept that is crucial to Syracuse’s zone: Know your opponent.

Syracuse gives up threes when playing the zone. They finish near the bottom in defensive three-point rate nearly every season. But in perimeter scramble situations a key for the Orange is to shade towards the best shooters on the floor.

To stick with the examples above, Buddy Boeheim can afford to be late on his close-out to Beekman (a 24% shooter), particularly if it allows him to limit Sam Hauser (a 42% shooter).

The zone has its base principles, with the ability to adapt to opponent personnel.

— SPONSORED CONTENT —

Today’s newsletter is presented by The Power Rank — a FREE football analytics newsletter that strives to be valuable, concise and entertaining while providing data-driven betting information on the NFL and college football.

The Power Rank is written by Ed Feng — a Stanford Ph.D. in applied math — who applies that expertise to football betting and March Madness. Stemming from his work at Stanford, Ed has built a football projection model that has picked the winner in nearly 75% of college football games.

If the name sounds familiar, you probably have seen Ed’s work before. The Power Rank provides analytical information around March Madness; Ed also had me on his podcast in April to talk college basketball analytics and coaching strategy.

Sign up for The Power Rank newsletter (free!) to get access to data-driven betting information, or check out Ed’s recent article on an overlooked quarterback stat that heavily impacts the outcome of NFL games.

Further reading/viewing on the zone

Thank you for reading the Hoop Vision Weekly! And please don’t forget to check out our sponsor The Power Rank.

If you’d like to receive access to exclusive content and support Hoop Vision, please consider subscribing to Hoop Vision PLUS. For $10/month or $100/year, your subscription unlocks access to exclusive offseason content and helps Hoop Vision stay independent.