The Quadrant System Must Go

The NET rankings have been a success, but that's only part of the overall equation.

With today’s release of the NET rankings, we have a special Monday article unlocked for ALL to read. Our usual Monday article — The Starting Five, five observations from the weekend of games — will be sent out exclusively to Hoop Vision Plus subscribers tomorrow.

Credit where it’s due: NET is good

Just over a year ago, the initial NET rankings were released to much scrutiny. Ohio State was ranked #1 (they finished #52), Loyola Marymount was ranked #10 (they finished #141), and Radford came in at #19 (they finished #137).

The rankings looked — at the time — objectively “wrong.” And to be fair to those criticisms, the NCAA didn’t exactly do much to alleviate the concerns.

The NCAA put out a tweet with “EVERYTHING” (they even used all capital letters) you need to know about the NET that, well, didn’t actually tell you everything you needed to know about the NET.

The machine learning component — Team Value Index — was (and still is) a mystery. The components seemed to have unnecessary overlap. Why use winning percentage and adjusted winning percentage in the same model? A big talking point for the NCAA was that scoring margin was capped at 10, but yet the number two component in the entire system — net efficiency — is just scoring margin divided by possessions. Was that net efficiency component capped in a similar manner?

Not only were these valid concerns, but they appeared to catch NCAA officials off-guard. The signs seemed to indicate the creators of the NET — or at least the decision-makers managing the creators of the NET — were unaware that the metric incentivizes scoring margin to the extent that it does.

But the season continued on and the sample size of games got bigger and bigger. Despite all of those questions and concerns, the NET rankings actually started to do a good job of predictively ranking teams.

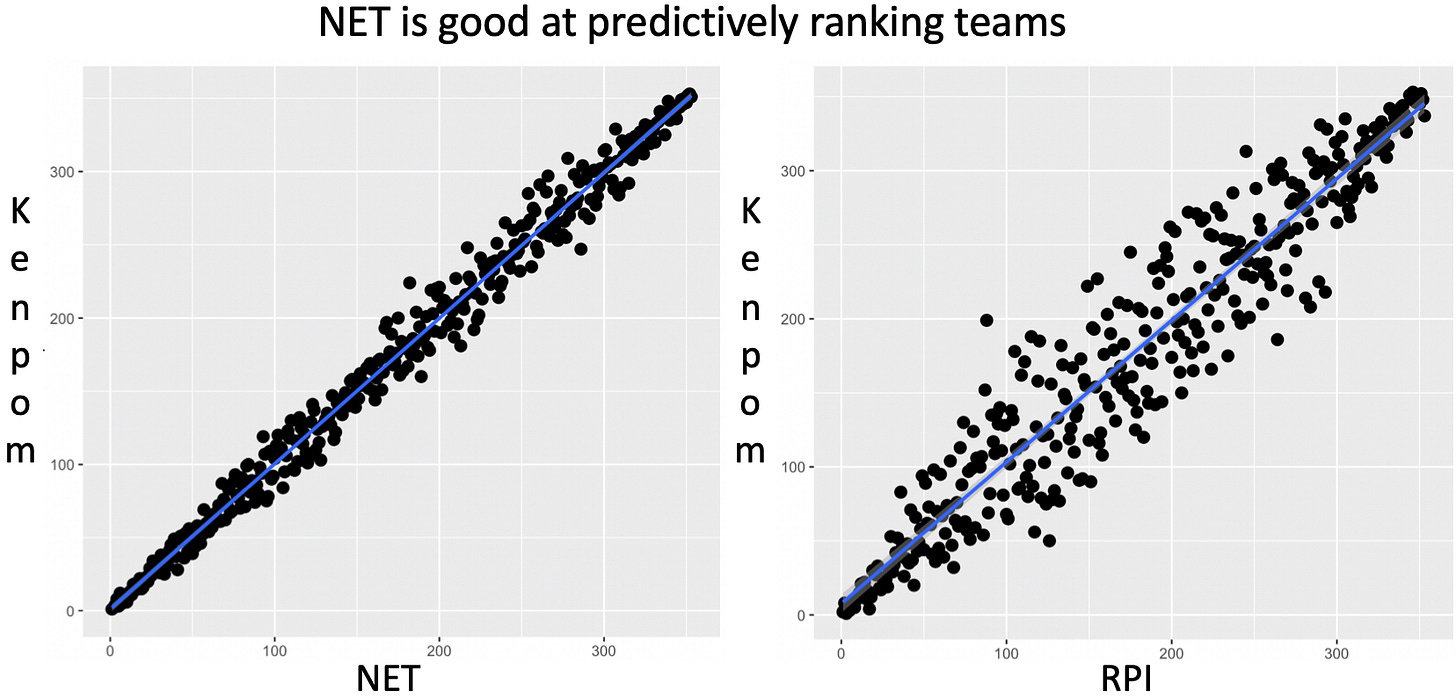

The graph on the left is the correlation between NET and KenPom last season. The graph on the right is the correlation between RPI and KenPom last season.

As you can see, NET and KenPom are very similar. The RPI is bad at predicting the future performance of basketball teams. The NET isn’t.

Ohio State, Radford, and Loyola Marymount weren’t ranked inaccurately because the NET is bad. Ohio State, Radford, and Loyola Marymount were ranked inaccurately because we are spoiled.

Early in the season, our go-to sources for predictive rankings use valuable preseason information. Some people like to complain when a team underperforms early in the season yet remains high in the rankings due to that preseason information (looking at you, Michigan State), but it’s that same exact information that allows these models not to overreact to the Radfords of the world.

We may still not have all the specific details to the black box nature of the NET, but we do have a year of results. And the correlation to KenPom — and in turn, the correlation to betting markets — tells us that the NET is a strong predictive metric.

Maybe most importantly, NET — unlike RPI — is very hard to game. There doesn’t appear to be a specific type of opponent that is systematically overvalued.

So what’s the problem here?

Well, Andy Katz summed it up perfectly back in March:

The purpose of the NCAA’s Evaluation Tool ranking (i.e. NET) is to sort teams into the four quadrants on the team sheets the men’s basketball selection committee uses for selection and seeding.

It is not a deciding factor.

It is not going to determine if a team is in or out of the bracket.

It is an organizational piece for the committee.

The quadrant system is not good

Evaluating a team’s resume is a two-step process:

How good was your schedule?

Given the answer to #1, how well did you perform against that schedule?

NET is being used by the selection committee to answer question one. It’s an organizational metric to determine schedule strength.

Because NET is better at predictively ranking teams than RPI, the NCAA is now better equipped to answer question number one. The problem is question number two — which relies on the quadrant system.

Instead of relying on NET to tell us exactly how strong a win or loss is, the quadrant system bins results into arbitrary categories. It’s a very human way of doing things.

On an episode of Solving Basketball last year, Ken Pomeroy said it best:

The fact that humans are trying to look at a 30-game schedule and evaluate what all those wins mean compared to another team's 30-game schedule and evaluate what all those wins and losses mean — it's an impossible task for humans to do.

The most immediate problem with the quadrant system is the arbitrary binning.

A win over the #1 team in the country and a win over the #30 team in the country are essentially the same

A win over the #30 team in the country and a win over the #31 team in the country are hugely different

The next problem with the quadrant system is that — like Ken said — humans are just not good at interpreting these resumes. How does the committee compare a team that went 4-8 versus Quadrant 1 opponents to a team that went 0-2? We’ll go back to Ken again for the answer:

You're basically judged on…What are your five best wins and what are your five best losses? You're still not going to get credit for beating teams in the 100 to 200 range like I feel you should if you can do that on a consistent basis over a 20-game league schedule.

The underlying metric being used to form the quadrants is now better after the change from RPI to NET, but the problem is the quadrant system itself. And in all of the mayhem regarding the roll-out of NET last year, that’s been lost in the national discussion.

For coaching staffs and schedule makers around the country, NET can’t be manipulated like RPI — but the quadrants can be. A system where resumes are systematically being evaluated incorrectly allows savvy teams and conferences to schedule towards those errors.

The selection process should be robust enough to evaluate a team’s performance fairly — regardless of schedule. But as it’s done currently, the selection process essentially has an opinion on how a team should schedule.

We don’t have a NET problem, but we do have a quadrant problem.

For more on the specifics of the quadrant system and (most importantly) a potential solution to move the selection process in the right direction, check out our video from October 2018: The Evolution of the NCAA Tournament Selection Process.