Hoop Vision Weekly: MAILBAG Edition (8/4/2019)

The post office was not prepared for all the reels of game tape you sent

Welcome back to Hoop Vision Weekly!

As the calendar rolls into August, we are officially in the most boring time of year for college basketball news. The NBA Draft has come and gone, players are either in summer school or relishing a couple rare weeks back home with family, and the July recruiting period has concluded.

Sure, August will see a mix of international tours, eligibility news, late transfers, major recruit commitments, and the like — but this slower month gives us a chance to explore some new topics and theories, share some ideas, and re-evaluate some assumptions about our sport.

This edition of Hoop Vision Weekly might help you do just that.

This is the first-ever “mailbag” edition of the Weekly. The past three weeks have been narrowly focused on defensive performance — how to quantify and account for the impact of a team’s defensive scheme, how to do something similar for an individual player, and three-point defense — but today we have a broader mix, based on select questions that were submitted.

Thanks to all who sent in questions. If you have any thoughts or questions after reading, please engage in the comments section of this email/post!

(If you’re reading on email and would like to comment, simply click/tap on the headline to open this in your browser)

Without further ado, let’s break open the big burlap sack of snail mail and get to it!

How would you advise an NCAA team to adjust to the new three-point line next year?

This question comes from the Kansas City Star’s Jesse Newell — and he wrote an interesting article on the topic to use as a starting point.

In that piece, Jesse used Will Schreefer’s shot location data from 2018, which filtered three-point shooting by distance. The NCAA average three-point percentage on NBA threes in 2018 was a very respectable 34.5% — not much of a drop-off from the 35.1% average on all three-pointers.

Jesse also found that the two teams to make the national championship that season—Villanova and Michigan—shot more NBA threes than any other teams in the sample (40% of all games).

That’s pretty good support for the idea that players will be able to adjust to the longer line without seeing a notable drop in efficiency, AND that—long term—the increased spacing will actually increase offensive efficiency.

I tend to agree that the impact of the deeper line will likely be negligible for strong or competent three-point shooters. Rest assured, the Markus Howard caliber shooters of the world will be just fine.

I do think it could have some type of impact on big men who were already marginal three-point options to begin with. College big men still take a much lower volume of threes than the “three-point revolution” would lead you to believe.

To get even more specific, it will be interesting to monitor both the usage and efficiency of pick-and-pop situations this season.

Last season, the NCAA average PPP on pick-and-pops was just 0.87 (compared to 1.17 on pick-and-rolls). The players most involved in those pops are the exact big men who might not be able to afford that extra inch or two.

Ultimately I don’t think we are talking about a huge impact here. And likely not enough where it should be changing a team’s offensive or defensive scheme or philosophy.

In Mike Waters’ Syracuse.com article with Ken Pomeroy on the same topic, Ken said:

“My gut tells me it’ll be a slightly good thing [for the Syracuse zone defense] in the short-term, but in the long-term, not so good. As players get used to the distance, there will be more area of the court to cover.’’

Short Answer: The impact on efficiency will be small, so most teams shouldn’t need to adjust their offense. However, one specific offensive action could see a disproportional impact.

How efficient is feeding the post in college basketball?

Should teams defend a dominant post player by doubling? Or by just letting him go to work 1-on-1?

I’ve been on record in the past about how the post-up is analytically misunderstood.

Yes, on average it’s an inefficient play type — similar to a mid-range jumper or isolation. But there’s an inherent upside to posting up which makes it unique.

There are a large portion of post-ups that involve some form of “ducking in” to seal or pin a defender. The primary goal of the duck-in is to get a layup. Coaches will often run some sort of misdirection to occupy the help defenders, thus maximizing the probability of an easy layup.

Last season, 56,399 recorded shots were taken out of post-ups. Those shots were classified in three different ways:

The player posting up turns over a shoulder

The player posting up faces up

The player posting up pins his defender

78% of recorded shots were classified as shoulder turns. These are what we usually think of when referring to post-ups. The NCAA average points per shot on shoulder turns was 0.90.

12% of recorded shots were classified as face-ups. The NCAA average points per shot on face-ups was 0.78. The low efficiency on these might be at least partially due to selection bias. I would guess a player is more likely to face up who is 1) farther from the hoop 2) not comfortable with back to the basket.

10% of recorded shots were classified as post pins. The NCAA average points per shot on post pins was 1.21.

The team that shot the most out of post ups last season was Lipscomb (417 shots). Not only were 21% of their 417 shots on post pins (above the NCAA average of 10%), but the Bisons scored a ridiculous 1.52 points per shot on those plays.

Even though post pins make up a relatively low percentage of total shots, the defense has to work hard to prevent them. Hard duck-ins and post seals are essentially another form of gravity.

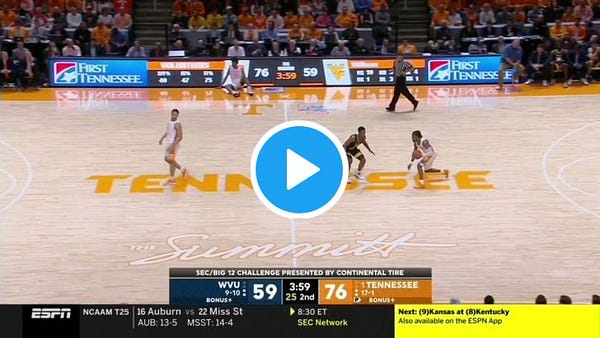

It’s difficult for an engaged big man who’s fighting to prevent from being sealed to then step up and be a help defender. Gonzaga (#1 in AdjO) and Tennessee (#3 in AdjO) both used this concept frequently last season.

So to get back to the second part of the question (“Should teams defend a dominant post player by doubling? Or just letting him go to work 1v1?”), I think that’s burying the lede a little bit when it comes to post defense.

How a team decides to defend early — fronting, playing behind, or somewhere in between — is maybe even more consequential to expected value than the decision to dig, play straight up, or double.

Very generally speaking, the data supports the idea of inducing post catches far from the hoop and then guarding one-on-one from there.

But playing behind in the post can put your help defense at risk on dribble drives. And there’s not necessarily a one size fits all depending on the personnel of your team and your opponent.

SHORT ANSWER: On average post-up efficiency is poor, but feeding the post contains a high degree of upside. And if you can prevent deep catches, the data appears to support playing 1-on-1.

Has there been any research done on three-point attempts in a game being an indicator of success? Or 3-pt attempts difference vs opponents?

Investigating something like three-point volume on a game-by-game level is tricky. Not only does correlation not imply causation, but late-game situations tend to confound things even further.

When a team trails deep in the second half, it’s likely going to lead to more three-point attempts for the team trailing, and more free throw attempts for the team leading.

That’s basically my way of saying that everything below should be regarded more as trivia, and less as conclusive analysis.

In the 2018-19 season:

Teams that shot more threes than their opponent won 49% of games

Teams that made more threes than their opponent won 66% of games

Teams that shot 10+ more threes than their opponent won 49% of games

Teams that made 10+ more threes than their opponent won 90% of games

Teams that shot less than 10 threes in a game won 56% of games

Teams that shot 30+ threes in a game won 51% games

The fewest three-point attempts in a win was four (Howard vs. American)

The most three-point makes in a loss was 22 (The Citadel vs UNC Greensboro)

While it makes for some interesting trivia, offensive threes attempted and defensive threes allowed should ultimately be viewed as independent of each other. The larger goal should be to maximize expected value on both ends. Whether that means shooting more or less than an opponent will largely depend on personnel.