Today’s article is unlocked for ALL — both free and paid — Hoop Vision subscribers as a peek behind the paywall of the content you receive with a Hoop Vision PLUS subscription. Join the HV+ community today for $10/month or $100/year for instant access to comparable articles such as:

“Oh yeah, we’re definitely gonna run”

There are two big factors that incentivize coaches to declare their teams will be dedicated to playing fast. First, it’s an attractive talking point for the fanbase. Fans like high-scoring offense. Second, it’s an attractive talking point for recruiting. Recruits also like high-scoring offense.

So a coach emphasizing how his/her team will be flying up and down the court is certainly logical from a “win the presser” standpoint, but what about a basketball standpoint?

In order to answer that question, the first step is to more accurately define how teams play fast. Playing fast is not a binary decision made by a coach simply with the snap of a finger.

Creating and converting advantages

At its core, offense is about creating an advantage and converting that advantage into points. One of the most common actions used to create an advantage against the defense is a screen. Other times, the thing responsible for creating an advantage is simply a player.

The first possible way for an offense to gain an advantage is with the transition push. Instead of waiting for the defense to get set, the transition push puts stress on the defense to get matched up early.

Data helps reinforce the inherent benefits of a transition push. Since the 2010 season:

The average points per transition play is 1.04

The average points per half-court play is 0.87

The graph below plots every team’s transition efficiency and half-court efficiency since 2010.

All the points above the diagonal line represent teams that were more efficient in transition than in the half-court. And, as you can see, that’s just about everyone. Only 64 teams fall below the diagonal line. In other words, 98% of all teams since 2010 have been more efficient in transition than in the half-court.

So why doesn’t everyone push the ball as much as possible?

The first thing to point out is that transition plays are naturally prone to a form of selection bias. The above transition data only includes plays where the offense: shot the ball, turned it over, or was fouled. It doesn’t include theoretical transition plays where the offenses wanted to push but was stalled out.

Another important factor here — which we will get into in the next section — is that all transition plays are not created equally.

The diminishing returns of the transition push

Transition efficiency is dependent on just how much of an advantage the offense starts with over the defense.

On a live ball turnover, that advantage tends to be the highest. For example, consider a point guard being stripped while bringing the ball up. A scenario like that one is very likely to lead to a high percentage dunk or layup on the other end.

Every team has a finite amount of these plays in a game which are (more or less) no-brainers to pursue with a transition push. It’s the plays where the offense doesn’t have nearly as clear of an advantage where a coach needs to determine an overall transition philosophy.

This philosophy is one place where extreme coaching styles can emerge. Carolina break-style coaches like Roy Williams employ their teams to turn “nothing-into-something” in transition. Even when the Tar Heels don’t have an immediate advantage, they push up the floor (in a fairly organized fashion) in an attempt to manufacture an advantage regardless.

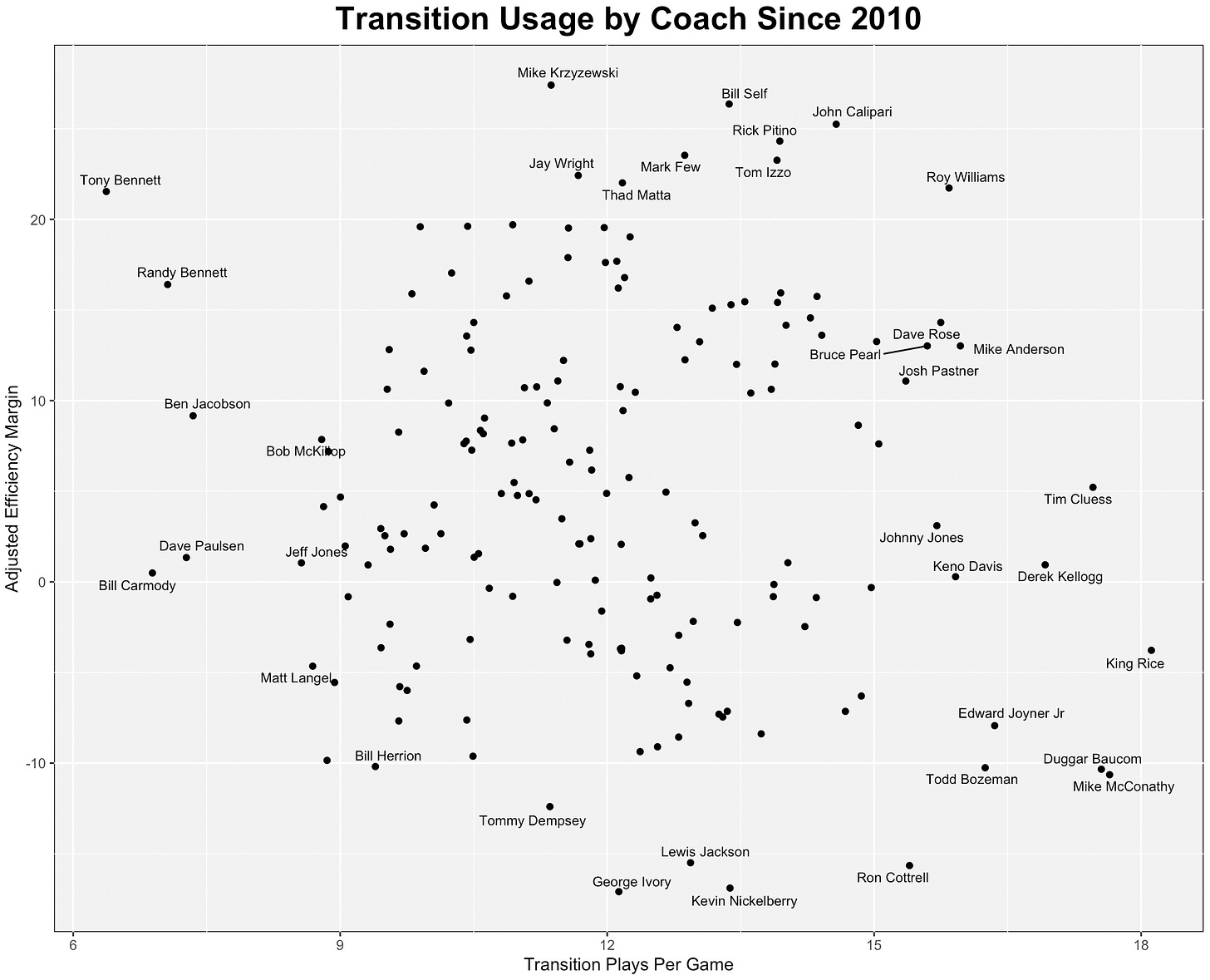

The graph below helps illustrate the different transition philosophies — with the most extreme coaches labelled.

There are well-respected offensive coaches on both sides of the transition spectrum. Tim Cluess and Dave Rose’s teams both average over 15 transition plays per game, while Randy Bennett and Bob McKillop’s teams both average under nine.

The coaches on the left are almost certainly leaving some points on the board by suppressing transition usage. But it seems possible they are getting some of those points back in other areas. A coach not on the graph — because he didn’t coach quite enough games over the time period to qualify — illustrates this transition trade-off the best.

In his final six years at Wisconsin, Bo Ryan averaged just 4.7 transition plays per game — the lowest of any coach. His teams were also among the most efficient (1.17 PPP) in transition.

Wisconsin was — and still is under Greg Gard — only pushing the ball in the no-brainer situations mentioned earlier. If the threshold for a transition push was lowered by Ryan, Wisconsin’s transition efficiency almost certainly would have decreased.

The other key factor here is the idea of “coaching equity.” Bo Ryan teams did several things unrelated to transition at an elite level. By almost completely ignoring transition offense, it may have in some ways enabled the Badgers to be elite at those other things.

This idea of coaching equity was best described by Fran Fraschilla in a recent Solving Basketball episode.

You just don't have time in a practice to be great at everything. So you have to pick out two or three things that you want your team to be great at on each side of the ball and you have to be proficient at the other things.

— Fran Fraschilla on Solving Basketball

Pace isn’t solely derived from transition

A willingness to push the ball up the floor in transition might be the most important factor to determining offensive pace, but it’s not the only factor.

First, let’s use the two most well-known active coaches associated with a slow or fast pace of play.

The x-axis above is the same transition plays per game metric we have already looked at, but the y-axis is different: Average offensive possession length.

As you would expect, the two variables are correlated — on average, teams with high transition volume have low possession lengths. That also holds true for Roy Williams and Tony Bennett, but not for every coach.

Coaches with fast half-court offenses

Fred Hoiberg and Bob McKillop are both examples of coaches with a shorter offensive possession length than would be expected given their transition volume.

In other words, Nebraska and Davidson play fast in the half-court. There’s not one exact half-court scheme to achieve that style, but a willingness to shoot threes appears to help. Both Hoiberg and McKillop have traditionally allowed their players freedom to shoot from deep.

Coaches with slow half-court offenses

Brad Underwood and Rod Barnes are both examples of coaches with a longer offensive possession length than would be expected given their transition volume.

In other words, Illinois and Cal State Bakersfield play slow in the half-court. For Underwood, that’s the result of his continuity-based Spread offense — which involves running the same actions repeatedly in a possession. In fact, his three slowest teams were all at Stephen F. Austin. Since moving to Oklahoma State and Illinois, Underwood has mixed in more standard ball screen action into his offense.

Rod Barnes is an example of what we might call “stall-ball” in the half-court. His teams aren’t necessarily afraid to push early in transition, but after that they take the air out of the ball.

In 2017, Barnes’ Cal State Bakersfield won the WAC regular season title and also made it all the way to Madison Square Garden in the NIT Final Four with the stall-ball.

So should you play fast?

To recap earlier points:

[1] Transition plays are the most efficient…

The average points per transition play is 1.04. The average points per half-court play is 0.87.

[2] …But there are diminishing returns

Creating an advantage out of thin air is much harder to do in transition than converting something like a 2-on-1 advantage from a live-ball turnover.

[3] Certain offensive schemes are great at maximizing transition volume…

For example, developing big men dedicated to rim running the floor on a consistent basis.

[4] …But coaching is a game of trade-offs

It’s nearly impossible for a team to be good at everything. Transition offense may or may not be the best thing for a team to emphasize.

——————

And to finish up, two more added points:

[5] Personnel obviously matters

There are certain players with skill sets — the most obvious skill being speed — that are optimized in open court transition plays. In general, good players in transition tend to still be good players in the half-court. But it makes sense that there are some extremes.

[6] The philosophy of passing up a good shot for a (potential) great shot has changed

Shot selection goes hand-in-hand with pace. The more strict a coach or team is regarding shot selection, the slower they will play. In the past, the idea of passing up a good shot for a great shot has been a pretty mainstream philosophy in coaching.

While that philosophy isn’t completely wrong, it has shifted with our understanding of modern efficiency. The idea that a great shot will actually come later in the possession is a big assumption. Instead, an offense might turn the ball over before finding that shot, or just wind up in a late clock situation.

In late clock (less than four seconds remaining on the shot or game clock) situations since 2010, the national average eFG% is just 36%. In total, late clock plays have produced just 0.70 points per play. Put in a different way, often times good shots are good enough.